My eyes grow dim, I cannot see, I cannot take good ukemi.

—Kenshusei summer camp ditty c. 1994, to the tune of “The Quartermaster’s Store,” a WW1 British Army song

. . . For here there is no place

that does not see you. You must change your life.

—Rainer Maria Rilke

Dear Sensei,

It doesn’t matter that the dojo is gone, rubble crushed to make way for a police station. This is no time for hesitation. I leave my zafu, climb the steps, bow from seiza, and enter your office overlooking Fairmont Avenue. The alchemy of scent conjures memories from the void: the rich fragrance of duck soup at the local Vietnamese restaurant, and, even more evocative, the aroma of cigarettes, Sen Sen breath mints, liniment, and whisky. I bow and enter the dragon’s lair.

I apologize for a ten-year delay in writing this letter when I could have mailed it while you were still present in this world. My excuse? The visceral, immediate nature of our connection makes it impossible to express myself with words. I should mention the bad bits, too, when anger and fear override gratitude; moments when “my eyes grow dim and I cannot see: I cannot take good ukemi.” While dark humor provides us reprieve from constant stress, you hate our Aikido Summer Camp song: “Too negative!” you scowl after we sing the ditty at another dojo party. Sorry if you bristle, but balance, honesty, and some humor, too (I recall your good cheer and easy laughter as well as your dark moods), are paramount if we want to reach the root of things. I know you admire Emerson’s essay “On Compensation,” where he states that too many people prefer a life of ease, seeking the mermaid’s head while ignoring the dragon’s tail. Finally, my gratitude embraces the whole of you, tail and all.

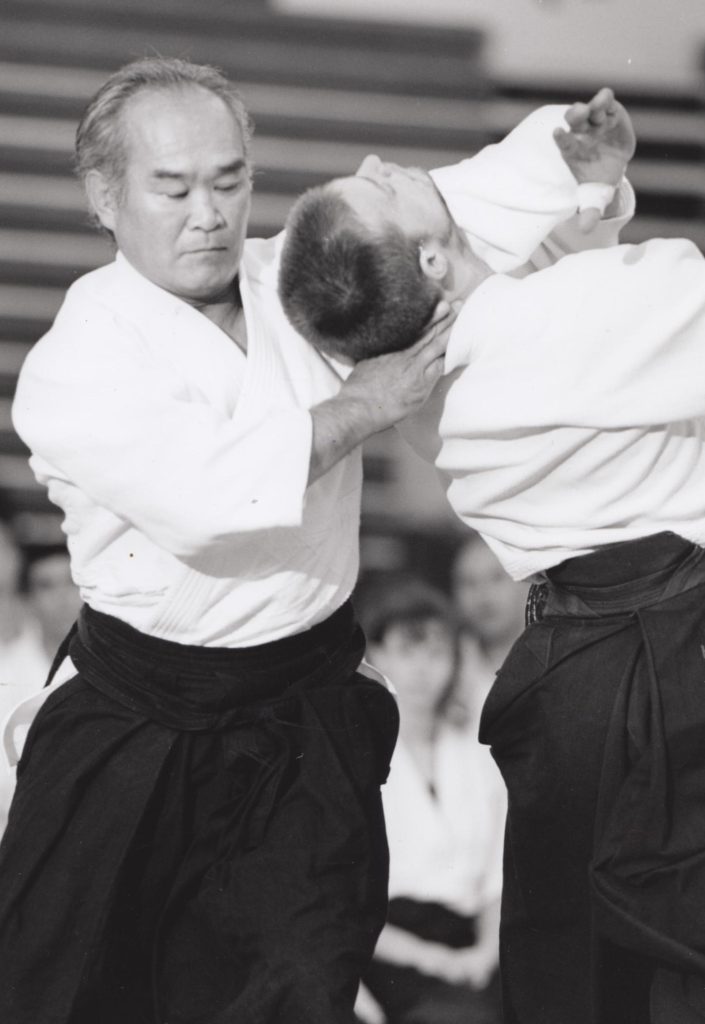

We have had a long relationship. I first saw you teach at USAF summer camp in 1983. I was thirteen, almost a year after beginning Aikido. I recall three things: Paul Sylvain and Lorraine DiAnne Sensei’s tiger’s grace and arrogance, and, on the last night of camp, I danced to the Ramones’ “I Wanna Be Sedated” in the Hampshire College cafeteria. And most of all, I remember your fire and presence. A chubby, ungainly teenager, I had no reference points for your Aikido—the only thing that evoked your intense grace was Toshiro Mifune’s swaggering ronin in a Kurosawa movie.

At the time I was fascinated by the chaos of punk rock and the disciplined clarity and rigor of Aikido practice. I discovered that I could be two somewhat contradictory people, both spiky rebel and receptive disciple. I had no idea that my path would bring me back to Hampshire College, where I trained with Sylvain Sensei (I chose the college in part because of the Aikido), and then I became kenshusei at San Diego Aikikai in 1994.

Why did I become your student when so many warned me to keep my distance? During my college years, at seminars you demonstrated tai sabaki (basic body movements) and yelled, “RELAX!” In these classes I discovered a profound wholeness—the sense of being centered within my body. I had never before experienced such a direct transference of unified energy. My love for your Aikido transcended the intellect; it was a direct reflection of this powerful sense of embodiment. Rilke, in observing the brilliant immediacy of a marble sculpture, declares that “there is no place / that does not see you.” In the poem, the poet enters art so deeply that one becomes both observer and observed: There is no place that does not reflect one’s experience, and, in the sudden shock of this moment, there is an existential imperative for transformation; in the very moment of wonder, you are already partially transfigured, made anew. Epiphany originally meant a direct encounter with divinity—an appearance and revelation beyond words or intellectual understanding. For me, your Aikido—in its intensity and emphasis on precision, alignment, and simplicity—was an epiphany.

After joining San Diego Aikikai, I recall both my courage and my fear. In the beginning, I have a nonchalant bravado regarding intense training. After too-slow ukemi and a powerful strike to my jaw, you ask if I am OK. It is before dinner; I can smell Mrs. Chiba’s fish frying in the kitchen, which makes it virtually impossible to focus on zazen. “Sensei, no carrots for a few weeks,” I reply, and we both laugh. Then later, after training for a few months, everything begins to turn grey; I recognize that this is my response to stress, but I didn’t know that fear actually has a color. How strange! I am afraid of your intensity, your arbitrary rage; perhaps even worse, my own self-criticism and sense of inadequacy magnifies my anxiety.

It is difficult to convey the feeling of being sucked into the vortex of your Aikido—at times it was like an electrical shock to my core. How do you keep connection and open your heart in the face of that fire? “You try too hard,” you said, and I took solace in the sense that there were worse things a teacher could say. And now, many years later? I take strength recognizing that I move toward spontaneity and simplicity within my own practice. That letting go after years of striving and wanting is a true blessing.

I leave your dojo early, no longer able to cope with your intensity and unpredictable moods. In my exit letter, I express my need for some balance: I want more than the dragon’s tail. Eventually, I attend your seminars again, still seeking something essential, still desiring our relationship on different terms. You ignore me for a while, and then at a seminar party you give me a big hug. Tears are in your eyes; I know that you grieve the loss of Sylvain Sensei, and I recognize your pain at losing me as a student. (Years later, I, too, recognize the mutuality of loss that we both experience as teachers when serious students leave.) Your hug makes me uncomfortable because, except for relaxed, amiable conversation during dinner, I feel like our relationship was always a martial encounter. “I am so sorry that your time in San Diego was so difficult.” And we renew our connection over seminars, camps, and, when I muster the courage, visits to San Diego Aikikai.

Eventually, when you gesture toward me and I rise to attack, stress remains—how could it not, given your intensity and the fast, unpredictable nature of technique—but the grey mostly disappears. And sometimes, on point, striking for the center of the circle, fire, focus, and fear bring me into the presence of something deeper where there is no separation, and the tatami rises to meet me. If you have eyes to see, if you have palms to feel: there are no words for these moments. Thank you.

Convention claims that you are no longer of this world, but we know otherwise; time doesn’t travel in a straight line, memory isn’t linear, and everything is contingent and ephemeral. I am being interviewed for your autobiography, and I try to gather words in the summer heat, but then I see you sitting zazen in your robes. You are staying at my house in Vermont following your seminar, and the dark basement door frames your stillness, the rain creating a veil, like a scene from Rashomon, and I am seized once again by the terrible inadequacy of language, and the depths of my gratitude. In the presence and weight of memory, with the immediacy of epiphany, I cannot speak. I reach across the grey and darkness, and in the brilliance of light, I grab your wrist. Just this.

Gassho (palm to palm),

Benjamin Pincus

Author’s Note: This Letter was originally published in a chapbook: “Remembering Chiba Sensei” printed in 2025 by Birankai North America in commemoration of the 10th Anniversary of Chiba Sensei’s passing. A special thank you to Roo Heins Sensei for her superb support and editing!